A growing population is changing the world and its values

A collection of climate stories mostly

I expect if you ask most people which country has the largest population most could be forgiven for saying China. They’d be wrong.

Back in April of this year (2023), China was quietly overtaken by India, which now has more than 1.4 billion people.

The success of the Chinese, one-child policy back in the 1980s, if you want to call it that, had significant consequences. Forty years later, the country has an ageing population in steep decline and an economic headache with all the signs of a more serious migraine.

Recent policies to incentivise Chinese women to have more children hasn’t helped. The average number of children per woman remains stubbornly stuck at 1.2, which isn’t enough to halt the decline and will result in a 10% fall in the Chinese population over the next twenty years. China is forecast to drop below 1 billion people before the end of the century.

The lowest birthrate in the world is 0.78 in South Korea. More or Less, BBC Radio 4, did a great bit of maths to explain the implication of being well below the birthrate of 2.1, the number of children needed per woman, to maintain the population.

If you take 100 South Koreans, 50 couples will produce 39 children to replace the 100 in the generation above them. Rounding it up, assume that the next 20 couples (40 not 39) will produce 15 grandchildren. In the next generation, roughly 8 couples will produce 6 great grandchildren. It helps to explain that Chinese headache and a striking change from the 1960s when South Korean women had 6 children on average.

If you wondering what has changed, the cost of child care is high, from the early kindergarten years to a place at one of the sort after private universities. South Koreans also work long hours and face expensive housing costs. Traditional values also ensure that few babies are born to unmarried couples and young women are putting off marriage until they’re older.

By 2050, the world will have about 10 billion people, up from just over 8 billion today (2023).

India and China will continue to be the billionaire population giants, with the US a long way back in third with 400 million and Nigeria, fourth, with a little less than 400 million. Following them are Indonesia, Pakistan, Brazil and Bangladesh with between 200-300 million people each.

Contrast this population explosion, with the latest UN figures I could find on global hunger, which date back to 2021. They make stark reading with 828 million people affected, up 150 million since the outbreak of COVID-19.

The World in 2050, written by Hamish McRae (nothing to do with the picture above) identifies three significant population trends. One is the ageing of populations in the developed world with some countries population declining. The second, is the shift in Asia from China to India and the third, the rising population of Africa.

Aging populations is nothing new. It is already happening in Europe and Japan, more slowly in the United States and now in China and Russia as well. Eventually, it will spread to India and Africa, but that is 50 plus years into the future.

Japan has the oldest population in the world, making it a helpful country to observe if you’re interested in the impact of population decline.

Many of Japan’s older citizens continue to do paid work long after retirement age. But this doesn’t prevent towns finding themselves with no children, so schools close, creating retirement communities, which are finally abandoned when effectively, there is no one left.

Japan maybe a calm, clean and crime-free country but it’s lost the economic dynamism prevalent in the 1980s. The most likely outcome is the economic stagnation which started in the nineties will continue indefinitely.

By 2045, there will be only 10 workers for every 7 retirees. Immigration could be one answer but the Japanese appear to have rejected this. The likely outcome is the young will have to accept a lower standard of living than their parents.

Italy has a birthrate of 1.35, very similar to Japan’s 1.4. They both suffer from high public debt and like Japan, Italy’s economy is barely growing.

Unlike Japan, Italy has experienced large scale immigration and emigration with a foreign-born population now exceeding 5 million. Perhaps more significant is the trend for young Italians to emigrate, mostly to northern European countries or the United States. It’s for a mix of social and economic reasons, typically driven by more opportunity, better jobs and faster promotion.

Spain and Greece have similar shrinking issues. And while it may appear to be a southern European malaise right now, it’s happening in Northern Europe too, just more slowly.

The Robert Schulman Foundation, a European research centre, describes Europe’s prospects by 2050 as demographic suicide. The relative decline of Europe is expected to lead to tensions with the United States, whose population will exceed Europe’s by the 2070s.

It will also be a different United States. It’s going to be older and more diverse, with the non-Hispanic white population becoming a minority. The foreign-born population, (14-17%) will be the highest at any time since 1850.

What will happen in Russia, is now an even bigger question? The predictions were that the country would need half a million migrants per year to steady its population. It is likely that Russia is experiencing net emigration now, which will lead to an even faster decline.

India had more people than China from the time of the Roman Empire to the start of the 18th century, when China accelerated away.

India’s booming young population brings new challenges. How does India’s government ensure that its children are better educated and trained for the jobs of the future?

The challenge is extraordinary. 10-12 million young people enter the Indian workforce every year, with 20% between the ages of 15-28 being currently unemployed. Creating jobs has to be one of the biggest challenges India now faces.

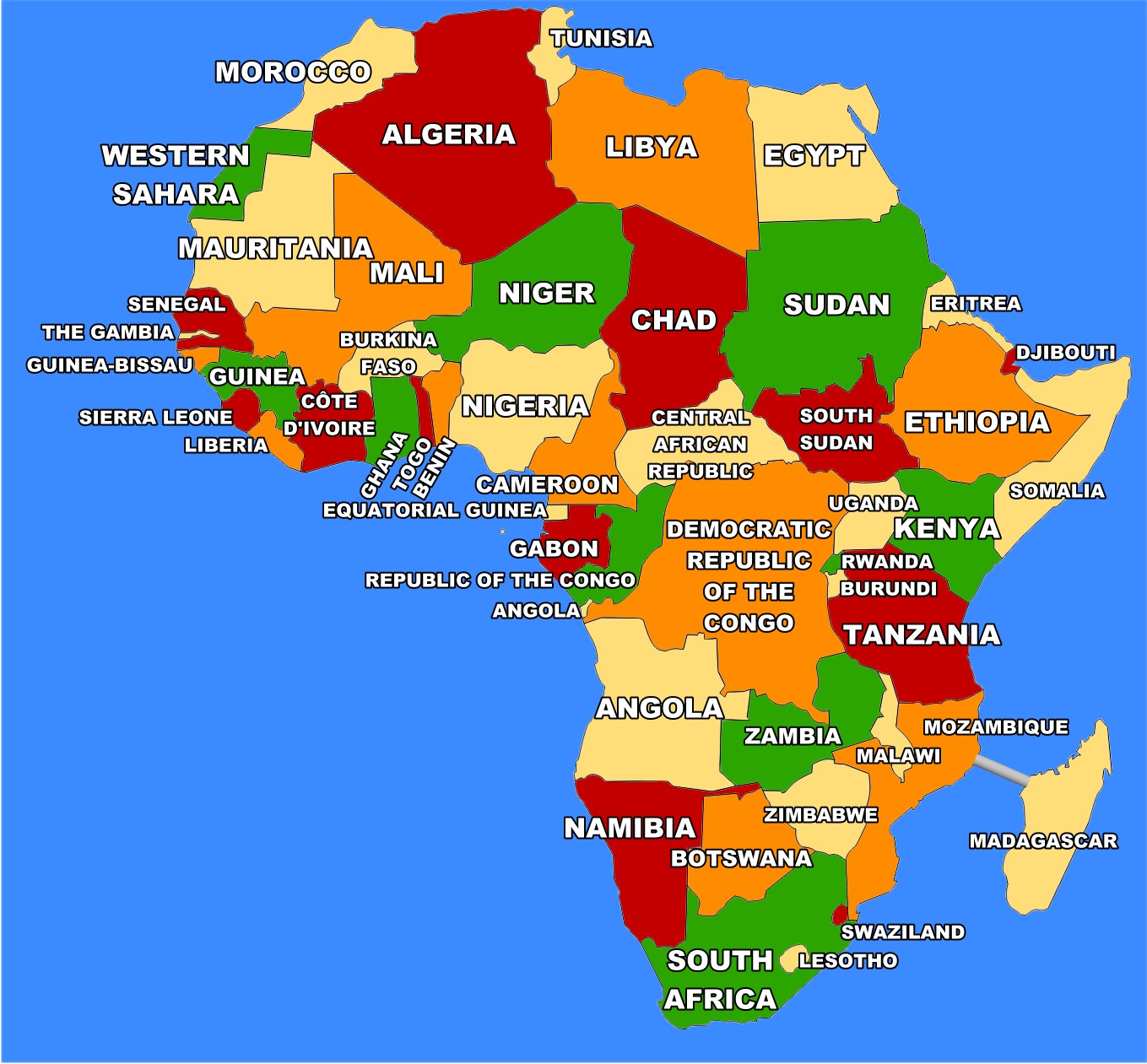

Most extraordinary of all will be the soaring population of Africa. The UN expects North Africa including the sub-Saharan region to account for a quarter of the world’s population by 2050, 2.5 billion people. By 2100, Africa will account for 40% of the total population. It will be young and hungry, while much of the rest of the world will be tired and old.

What sort of shift can we expect when the African people, the environment and their ideas of how societies should be organised all becomes far more important? One prediction is that young Africans will have better life chances within the continent, than if they were to leave. For that to happen, there needs to be inward investment which is notably already happening, courtesy of China and emigrants remittances back home.